Day Ten -- Seeing More Sights Around Taos NM -- 14 August 2010: Our friend Dave and Hostess Annie put together another day of sightseeing around Taos and then joined us.

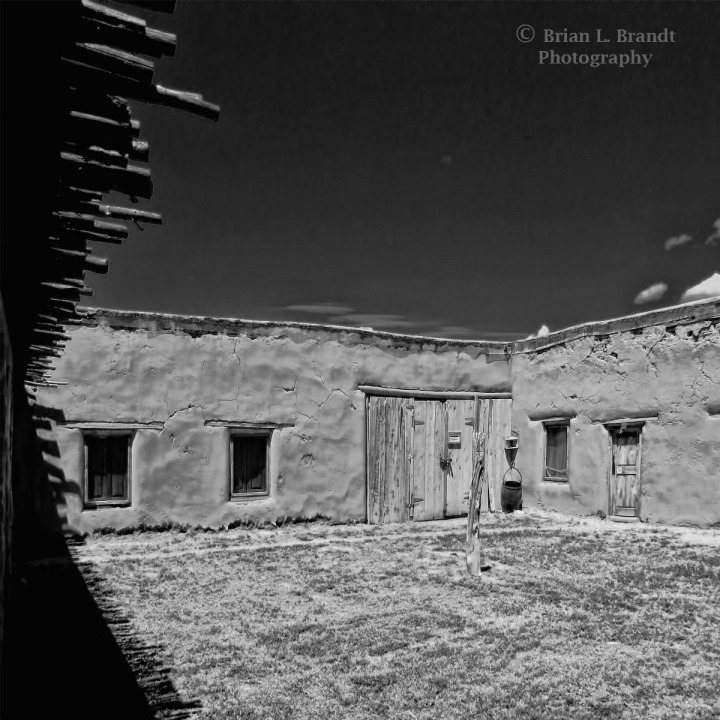

Our first stop was at the Martinez Hacienda, dating from 1804.

The Hacienda is on the National Register of Historic Places by the United States Department of the Interior. The Hacienda de los

Martinez is one of the few northern New Mexico style, late Spanish Colonial

period, “Great Houses” remaining in the American Southwest. Built in 1804

by Severino Martin (later changed to Martinez), this fortress-like building

with massive adobe walls became an important trade center for the northern

boundary of the Spanish Empire.

Today the Hacienda’s twenty-one rooms surrounding two courtyards provide the visitor with a rare glimpse of the rugged frontier life and times of the early 1800s. The Hacienda was the final terminus for

the Camino Real which connected northern New Mexico to Mexico City. After Mexican Independence from Spain in 1821, Severino Martinez and his family became active in trading with the Americans who were bringing badly needed trade goods in by the Santa Fe Trail.

The

Hacienda also was the headquarters for an extensive ranching and farming

operation. Severino and his wife

Maria del Carmel Santistevan Martinez raised six children in the Hacienda.

Because of the tenuous nature of life on the New Mexican frontier, the hacienda was surrounded by a thick protective adobe wall. Inside the hacienda, the bedrooms were spare and austere. The interior courtyard was large enough to accommodate the livestock in case of attack. In the early 1800's, everything was hand forged, from the basketwork to the locks and latches.

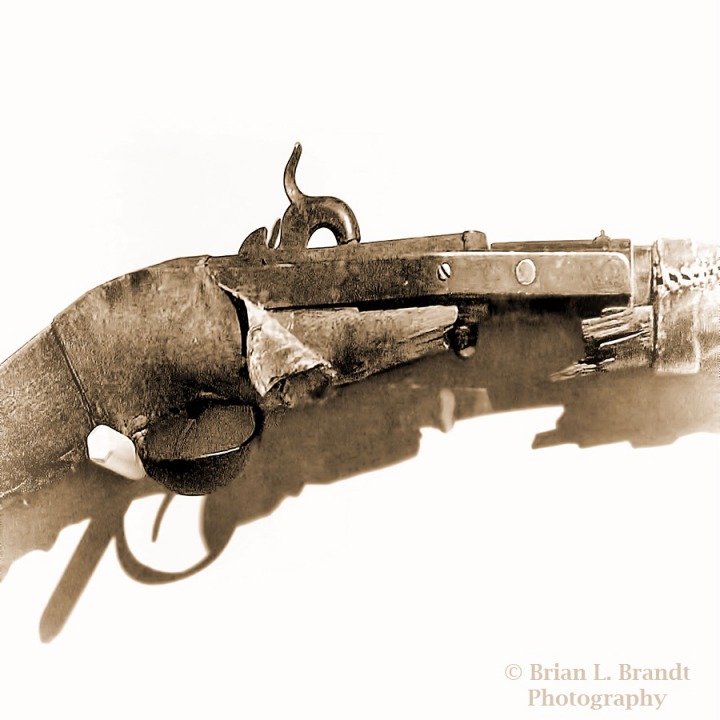

The interior walls were constructed in a number of steps and layers. Among the features of the house and tack room were a hand-forged hinge (with the adze marks from finishing the planks still in evidence on the doors) and a hand-braided lariat, from what looks like cotton. Lariats from the early 1800's would have been made of leather, agave, or braided, spun cotton.Like everything in the hacienda, the doors were hand-jointed, glued with hide glue, and hand carved. It was anything but a throw-away society, so even smashed flintlock rifles were patched -- sometimes even using strips of leather to hold them together.Because the one thing you do not want to run out of during an attack is water, the well was inside the hacienda courtyard. Transportation was by ox or donkey cart -- the one below resting near the wall in the mid-day sun with a long shadow cast by a drain spout in the wall. The oxcart or donkey cart wheels did not have spokes -- instead they were cut out of sectioned, glued wood rounded for rolling. The Martinez's eldest son was the famous Padre Antonio Martinez who battled the French Bishop Lamy to preserve the Hispanic character of the Catholic Church in the territory. Padre Martinez was a dynamic social reformer who created the first co-educational school in New Mexico and brought the first printing press to Taos.

Tortured, bloody iconography was part of the deeply rooted Catholic tradition of the Southwest. The interior courtyard was surrounded on two sides by a covered passageway that protected the occupants from the direct heat of the mid-day sun. Saddles, like everything else, were hand-crafted and rock hard. Twelve hours in one of these saddles chasing half-wild longhorns would prove or break a man. While a lot of things were precious where resources were so scarce and hard earned, socks, as it turned out, were particularly valued. A wooden form was created for each family member, then socks were knit individually for each person. Socks were so important and hard to come by, they were specifically called out in wills. Everything for the home was hand-constructed, and the wheat or corn from nearby fields, or from trade, had to be ground locally. The Martinez family had their own stone grinding wheels, originally a matched set, top and bottom, probably "propelled" by a donkey walking in circles on the end of a large pole. One imagines that a hand-felted sombrero, the last bastion against the punishing sun, was as valued as the hand-knitted socks. And handy for waving goodbye to visitors.From the Martinez Hacienda, we stopped by the Harwood Museum in Taos.

Artists Flock to Taos -- In

the early part of the 20th Century, many artists were drawn to the Taos area to

pursue a new, truly American art devoid of industrial influence, inspired

instead by New Mexico's landscape and light and the traditional Native American

and Hispanic cultures of the region. The

Harwood Museum collection brings to the public a unique record of this artistic

convergence from its beginnings to the present day.

The Harwoods -- Artists Burt and Elizabeth Harwood left their residence in France and moved to Taos in 1916. They bought property, and by 1918, The Harwood complex, then called El Pueblito, was on

the forefront of the Pueblo/Spanish Revival and restoration movement in New

Mexico. Discovering that Taos had no library, they established the Harwood Library by 1926, and the community generously supported the growth of its collections. Mabel

Dodge Luhan donated books from her private collection, contributed funds, and

inspired other major support.

University Involvement -- In

1935, the Harwood Foundation was given to the University of New Mexico (UNM).

As part of UNM, the Harwood received core support from the University and

functioned as a base for University programs in Taos County.

Harwood Expansion -- In

1937, UNM and the Works Projects Administration (WPA), working in cooperation

to create an enhanced facility, embarked on a major expansion and renovation

project of the Harwood complex. Designed by John Gaw Meem, one of the best

known architects of the Southwest, the Harwood addition became one of the

tallest adobe structures in northern New Mexico, and included an auditorium,

stage, exhibition space, and a library facility. It now houses a very nice collection. Two of the pieces that caught our eye were this cabin tucked at the base of the New Mexico mountains, and a painting that was one of Dave's favorites in the museum. It was dark in the museum, and they didn't like "Flash" so we didn't take many photos.

From the Harwood, we went to the Couse/Sharp Historic Site and the house where artist E. Irving Couse had his studio and his salon of fellow Taos artists.Much of our information below is from that site.As It Was -- In the Couse house, nothing is under glass. It all remains as it was a hundred years ago, and you can almost imagine that Couse stepped away from his easel for a cup of tea.

The Couse house is still furnished with the original furniture and household items that belonged to the artist. The Couses' collections of early New Mexico furniture and Santos, Blue Willow china, and objects of copper, brass, and pewter decorate the living room and dining room.

Taos Gets "Discovered" -- In

September of 1898, Ernest Blumenschein and Bert Phillips, two young artists

from New York, discovered the beauty and fascination of the Taos Valley of

northern New Mexico. Their experience with art colonies in Europe stimulated a desire to

establish such a colony in Taos. There the landscape, the Native American and

Spanish cultures, and the spectacular light caused Phillips to say to

Blumenschein, "For heaven's sake, tell people what we have found! Send

some artists out here. There is a lifetime's work for twenty men." Couse

was their first convert, arriving in 1902 and returning every year thereafter.

Taos Society of Artists -- By

1915, six professional artists from the East had made Taos a focus of their

work. In that year they formed the Taos Society of Artists, sending circuit

exhibitions of their paintings across the country and exposing audiences to new

cultures, new visions, and a new landscape. This put Taos "on the

map" for art and tourism, making it one of the most important art colonies

in America.

The Society lasted until 1927, by which time there were twelve active

members which included: Bert Phillips, Ernest Blumenschein, Irving Couse, Henry

Sharp, Oscar Berninghaus, Herbert Dunton, Julius Rolshoven, Walter Ufer, Victor

Higgins, Martin Hennings, Kenneth Adams, and Catherine Critcher. Prompted by the reputation of the Taos Society

of Artists and later enhanced by the presence of the art patron, Mabel Dodge

Luhan, the art community expanded rapidly.

Friends

and Colleagues -- The

Couses and the (Henry) Sharps first met in Taos in the early summer of 1906. A special relationship began to develop

between the two families when the Sharps bought property on Kit Carson Road in

1908, and the Couses moved to the adjacent property the following year. Both artists built large studios which today

are the best surviving examples of what studios were like in the early art

colony.

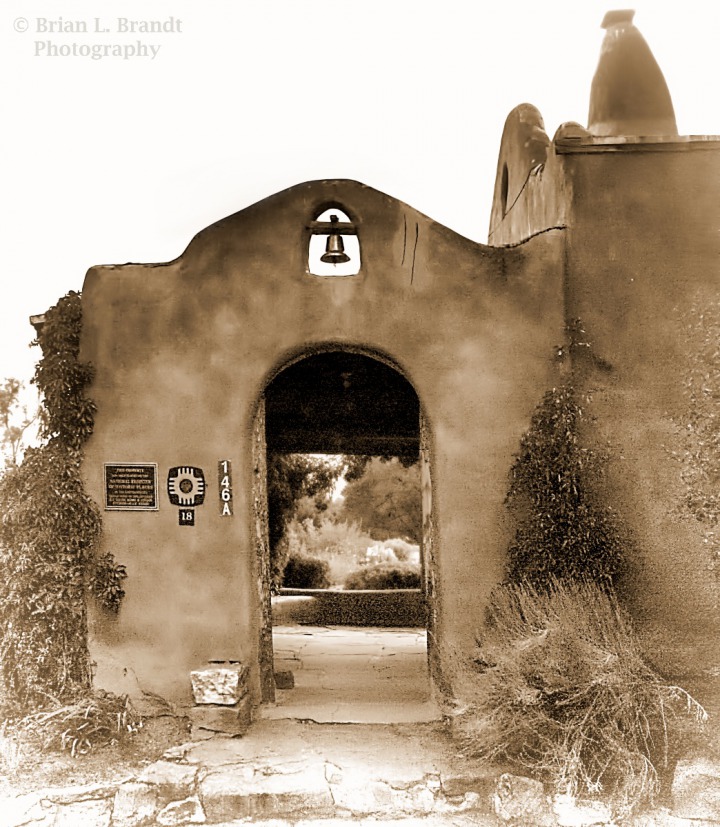

To the side of the entrance to the house is a bell from 1868, which may or may not have been used to announce arriving guests. Like many of the houses in Taos from that era, the construction was multi-layered and complex, using wood, adobe mud, straw, and other local materials.Couse worked in conditions that had decent light, but no padded office chairs -- not much in the way of creature comforts. The artist's studio still remains a magical place. It contains the Native American pottery, costumes, beadwork, and other artifacts, that he used in his paintings. In the corner an unfinished painting and his artist's brushes and palette seem to await his return.Couse painted a lot of southwestern themes, including paintings of painters. Couse had several easels, including one that raised up considerably for working either sitting or standing or for working on larger pieces. Couse had what was probably a very expensive set of brushes, which I'm sure he cared for with delicate pride, since getting new brushes in Taos in the early 1900s was non-trivial. Like many of the Taos houses of that period, there were covered walkways along the patio and garden areas to spare the residents from the worst of the direct blast of the high New Mexico sun.One can imagine Couse, sitting in his Taos-blue rocker, chatting with fellow members of the Taos art colony and sipping something cool in the hot Taos summer evenings. The Site is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

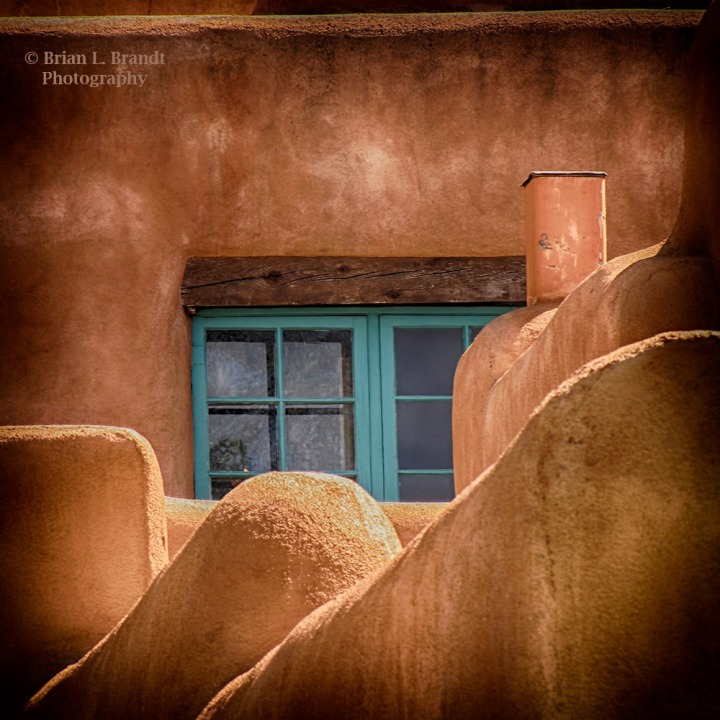

After leaving the Couse house, we strolled around the immediate neighborhood of Taos, looking at the adobe construction and the classic Taos Blue trim. Here and there, blooms offered a texture and color contrast to the adobe and Taos blue trim. Even the gates in the area were works of art in their own right.We walked into the evening, and then drove back to Annie's house for dinner and nightcaps.

Text by Brian and Louise with Photos by Brian. Text and Photos Copyright by Goinmobyle, LLC. 2010.