Day Five -- The Million Dollar Highway CO, 9 August 2010: After spending two days at the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park outside Montrose, we headed for Pagosa Springs via Ouray, Silverton, and Durango on US HWY 550, also known as the Million Dollar Highway. We drove in a hard rain most of the way, but even that didn't take away from the spectacular scenery and color that all the mineralization provided in the area of Red Pass between Ouray and Silverton.

Ridgway CO -- One of the first landmarks we hit outside Montrose was Ridgway, with a state park, a lake, and a massive ridge beyond. We don't know where they lost the "e" in Ridg(e?)way over the years. It sits just shy of 7,000 feet. Ridgway started in 1891 as a link on the Rio Grande Southern Railroad and served as a supply center for the mines scattered through the San Juan mountains. Rail service stopped in 1951. The movie

True Grit with John Wayne was filmed here in the 1970s. The nearby recreation area surrounds a 1,000 acre reservoir on the Uncompahgre River.

Between Ridgway and Ouray, the country quickly turns to narrow canyons surrounded by soaring peaks as the highway follows the Uncompahgre River. Uncompahgre means "hot water spring" in the Ute language.

Closer to Ouray, the rock turns crimson -- as the canyon narrows, it's right outside the car windows. These are Triassic, Permian, and Pennsylvanian redbeds of sandstone and shale formed over a 120 million year period as volcanic ash from the north washed off the high mountains and formed layers in the valley.

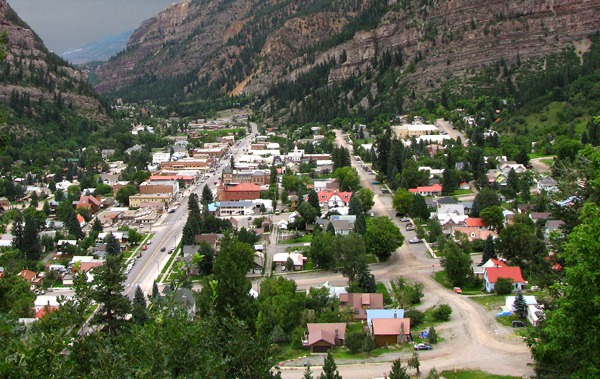

Ouray CO -- One of the first things we noticed about Ouray is that mining continues apace -- it appeared they were mining gravel from a creek bed as we drove into town -- but we actually have no idea what they thought they were doing in there.

In August, there was no snow left on the slopes of the narrow canyon in which Ouray rests, but we could imagine avalanches shooting down the steep canyon sides which were with what appeared to be avalanche chutes. That didn't seem to bother the real estate developers who built houses in the chute paths!

The shot below of the public pool (water temperature 104 degrees) gives a little idea of the setting for Ouray. They bill themselves as the Little Switzerland of America. The town is in a narrow valley at an elevation of 5,000 feet; the surrounding peaks are 12,000 and 13,000 feet high. Both gold and silver are mined here; mining started in 1875.

Chief Ouray -- The town is named for Chief Ouray, a southern Ute chief. He was born 13 November 1833 in Taos NM to a Jicarilla Apache father and a Ute mother. On the night he was born, there was a meteor shower. This event influenced his parents to name him Ouray, which means "the arrow."

The downtown has a lot of old mining era buildings with restaurants and other tourist attractions such as hot spring pools. Ouray has somewhere around 1000 permanent residents. US HWY 550 south snakes its way up the face of the hill in the background at the end of town and then into the canyon beyond.

One of the most spectacular things we saw in Ouray was this garden tiger moth on a leaf at the nice little visitor's center. Leesha got out and gave everything a good sniff.

During the climb out of the Ouray valley, you get a better sense of the dramatic ridges that surround the town.

There's what one might call "the pull up out of Ouray" -- especially if you are driving a big rig. Eight percent grade and no guard rails. Let'er buck.

Million Dollar Highway -- There are several stories about the name for US HWY 550 -- The Million Dollar Highway -- what it cost per mile to build it back in the day when a million was real money or it was paved with gold-bearing gravel or that's what they would have to pay you to drive it in a blizzard. It's what one might call a "hand hewn" highway -- hands and a whole bunch of dynamite. It started out as a toll road built in the 1880's by a guy named Otto Mears who must have been one tough old dude with a penchant for high explosives. At the behest of surrounding county governments, he eventually built 450 miles of toll roads in the San Juan mountains before switching his interests to building railroads.

When you look at the canyon walls you get some sense of what the first engineers who started hacking this road out of the canyon sides saw. I can imagine a bunch of them standing around with their hands in their pockets eyeing each other while a foreman says, "We're puttin' it right through there, boys."

Mining -- All along the road, you see evidence of poking and probing to see if there's something worth hauling out.

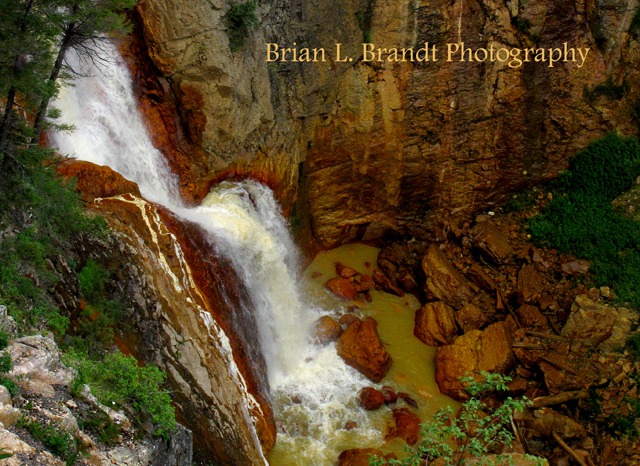

Many mines here worked small, pipe-like ore bodies of silver, copper, and lead. Underground, mine tunnels honeycomb the area. The area is obviously highly mineralized, and now the rivers in the area run in Technicolor as toxic minerals seep out of the abandoned mines. Don't drink the water.

Red Mountain Pass -- As we kept climbing, the clouds swirled the peaks on both sides of the road.

Out of the clouds arose the startling colored peaks that flank Red Mountain Pass, the 11,018 foot pass that forms the divide between Ouray and San Juan counties on the way south to Silverton. Iron oxide rules on the pass.

At this altitude (over 10,000 feet) the wildflowers were still in force along the road.

There was also a profusion of nice, tender green grass -- one of Leesha's favorite parts of traveling. Louise stands by while Leesha samples some of Colorado's greenest.

Evidence of the mining of yesteryear was everywhere you looked as we neared the top of the pass.

With all the prior mining activity, the technicolor river syndrome was in evidence everywhere near the pass.

The rain on the pass wasn't mineralized, luckily, and the plants loved it up there.

And more evidence of old mining activity abounded.

And then we got to the actual Red Mountain Pass.

We started down off the pass and then something caught our eye down over the edge of an embankment -- a marmot hoping for a sun patch to pass overhead.

It was worth your life to go back and get a photo -- no shoulder on the road and the only parking spot for two miles left a portion of the rig in the road. But the marmot was obviously used to being unmolested and didn't blink an eye as it was captured -- digitally.

We started down the Silverton side of the pass, and it was just as scenic going down as it had been coming up.

Silverton CO -- Here the road enters the Silverton Caldera, one of many formed in the San Juan Mountains. Calderas develop during or after explosive volcanism, when a roughly circular area collapses into a partially emptied magma chamber below a volcano. This caldera has produced more than $150 million in silver, gold, lead, copper, and zinc. Up a side canyon right at this road curve were a couple of long and spectacular waterfalls and cascades.

We were getting close to Silverton -- hard to believe that it was only 23 miles from Ouray to Silverton and a theoretical 40 minutes or so. It seemed we'd been on the road half the day from Montrose already -- there were so many photo ops. The scenery as we approached Silverton was amazing, and the sun started to poke through the clouds now and again.

Silverton is tucked into the tiny canyon between that red outcrop above and the towering peak beyond. As we got closer to Silverton, I took another shot of the angry red outcrop.

And at last, Silverton. We'd burned so much daylight already, we decided to admire it from afar. Silverton is at an elevation of 9,300 feet in a tiny pocket between Red Mountain and Molas passes. It started as a mining camp in 1871 and was so wild that the town recruited Bat Masterson to clean it up. Today the area still relies on local mines and tourists, The Durango and Silverton narrow gauge railroad runs between the two towns; hikers and backpackers enter the Weminuche Wilderness Area here; jeep tours cross Engineer and Cinnamon passes on the Alpine Loop, and the downtown walking tour provides a slice of mining history.

After passing Silverton, we encountered some road construction that had traffic stopped. That offered us two opportunities.

Electra Lake and Road Construction -- The first was to admire Electra Lake and the peaks beyond it which would have been a challenge to see adequately even at US HWY 550 speeds, and the second was to talk with the woman holding the Stop/Slow sign. She drove 100 miles or so to this job every day, but it was only one of the three jobs she worked at every week which including managing a small dairy herd. Apparently, if you don't live in Denver, or have access to a trust fund, Colorado can be some tough livin'.

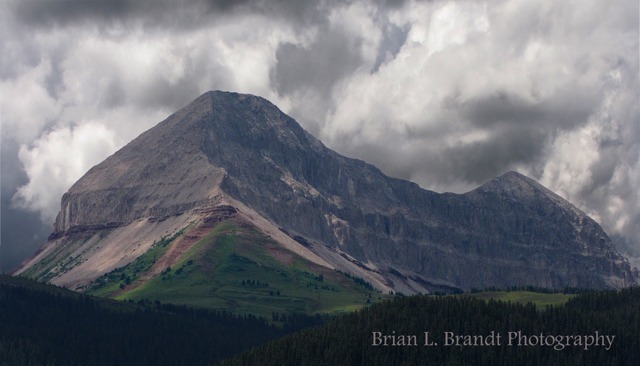

As we got closer to Durango, we saw several sort-of stand-alone peaks there that were very impressive -- one in particular, Engineer Mountain, loomed large. At just a tick under 13,000 feet, it dominates the area around it more than it would if it was just a high point on a 13,000-foot ridge other places in Colorado.

Engineer Mountain Hike -- From Trails 2000 (a non-profit organization based in Durango, CO): "this is a favorite hike or ride that is well marked and in close proximity to Durango, making it quite popular in the summertime. Engineer Mountain is the prominent “double” cone which can be seen when driving northbound on US HWY 550 beyond Purgatory in the San Juan National Forest. It is a fun and challenging mountain with awesome panoramic views in all directions from the summit, since it’s nearly 13,000’ and stands alone. The most direct ascent starts at Coal Bank Pass on Hwy 550 and goes up the Pass Creek Trail. While only 4.4 miles round trip, it’s considered a difficult climb due to the narrow ridge, loose talus, and the exposed crux move." Also, be aware of lightning hazards during afternoon thunderstorms; it would be prudent to start your hike early.

As we passed Engineer Mountain and dropped down into Durango, we decided that we'd dallied long enough and started to press on to Pagosa Springs so we wouldn't make it in after dark. You could easily spend a couple days making this drive -- if you are camera-inclined. Even on a rainy day it was amazing.

Text by Brian and Louise -- Photos by Brian. Text and Photos all copyrighted Goin Mobyle LLC 2010

Resources: Chronic and Williams. Roadside Geology of Colorado, 2nd ed. 2002; Metzger. Colorado Handbook. 1992